Where will the electricity come from when the wind is not blowing?

Not a day goes by without Jukka Ruusunen, Fingrid’s CEO, hearing this question from a wind power sceptic. He always gives the same answer:

“Unless we invest in wind power, we will not even have electricity when the wind is blowing.”

The rapid development of wind power technology has Ruusunen convinced: “Ten years ago, I did not believe that things would develop this quickly.”

He says that wind power is the only way to quickly clean up heating and transport by eliminating the carbon dioxide emissions that are accelerating climate change. Wind power would also promote self-sufficiency as Finland currently imports one-quarter of the electricity it consumes.

Ruusunen praises the programme for Antti Rinne’s government for “paving the way towards a clean, cost-efficient power system, without forgetting the security of supply”.

“If the Government is able to implement the programme’s objectives, Finland will be a pioneer in implementing energy solutions.”

“Jukka’s package”

Ruusunen sets out a model for freeing Finland’s electricity generation from fossil fuels in around ten years.

“Jukka’s package” is based on nuclear power. The completion of the third reactor at Olkiluoto power station will increase the nation’s power output by 1,600 megawatts.

The next piece in the puzzle is combined heat and power (CHP) generation in cities and industries. The proportion of this form of generation is, however, becoming substantially smaller as cities are increasingly switching to generating heat alone.

Ruusunen also keeps hydroelectric power in the mix. Hydroelectric power is needed as a form of balancing power, although no major hydroelectric plants are likely to be built.

Ruusunen points to a significant increase in wind power construction as the primary form of new power generation. In his vision, the electricity generated by wind turbines could account for over 20 per cent of the total by 2030.

“The wind power projects currently underway would add more than 15,000 megawatts of generating capacity. If half of them come to fruition, wind would become the second-largest form of generation after nuclear power.”

Over time, we will also have to move away from peat: “We need to give up peat in a managed way without jeopardising the security of the heat supply.”

Wind power all over Finland

Ruusunen says that the battle against climate change must be fought in the most economically efficient manner possible. He praises Germany for the billions it has invested in wind power, which has contributed to the development of the competitiveness of wind power.

“Wind power used to be expensive. Now it is viable on an industrial scale without subsidies. The price of electricity generated by wind power has come down to EUR 30 per megawatt hour.”

“The price of nuclear power would have to fall by half to compete with wind power. Is nuclear power capable of such a dramatic change in competitiveness within the current safety requirements?”

Wind power also comes up against resistance. For example, the maintenance routes built to provide access to wind farms on the fells of Norway have damaged sensitive natural habitats.

According to Ruusunen, the demands of nature protection, tourism and reindeer husbandry may prevent wind power from being built on a large scale in Lapland: “Finland does not need Lapland’s wind power as such, but the municipalities in Lapland could do with it.”

He points out that wind farm companies pay taxes to municipalities. The landowners who permit towers to be constructed on their land also receive an income: “By some estimates, this could amount to EUR 15,000 per tower per year. This is claimed to be a better business than managing forests.”

“It would be easier for Fingrid if all of the wind turbines were in the south of Finland because that is where most of the consumption occurs. It would not be necessary to build as many large power lines.”

Making a good government programme a reality

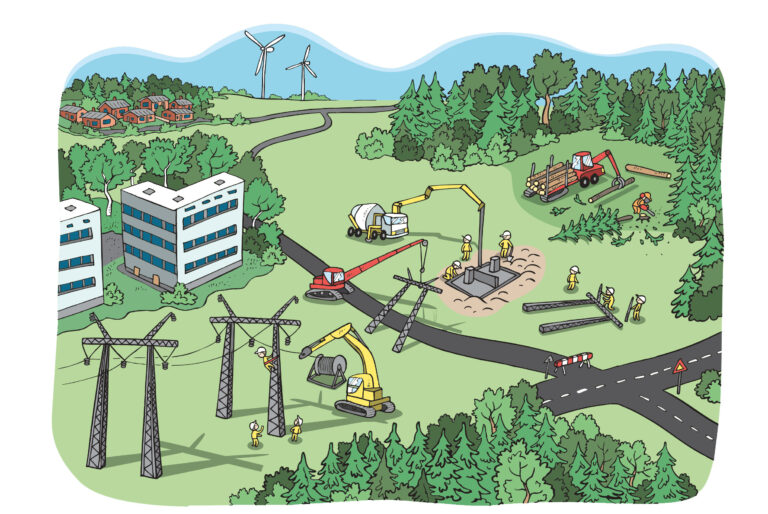

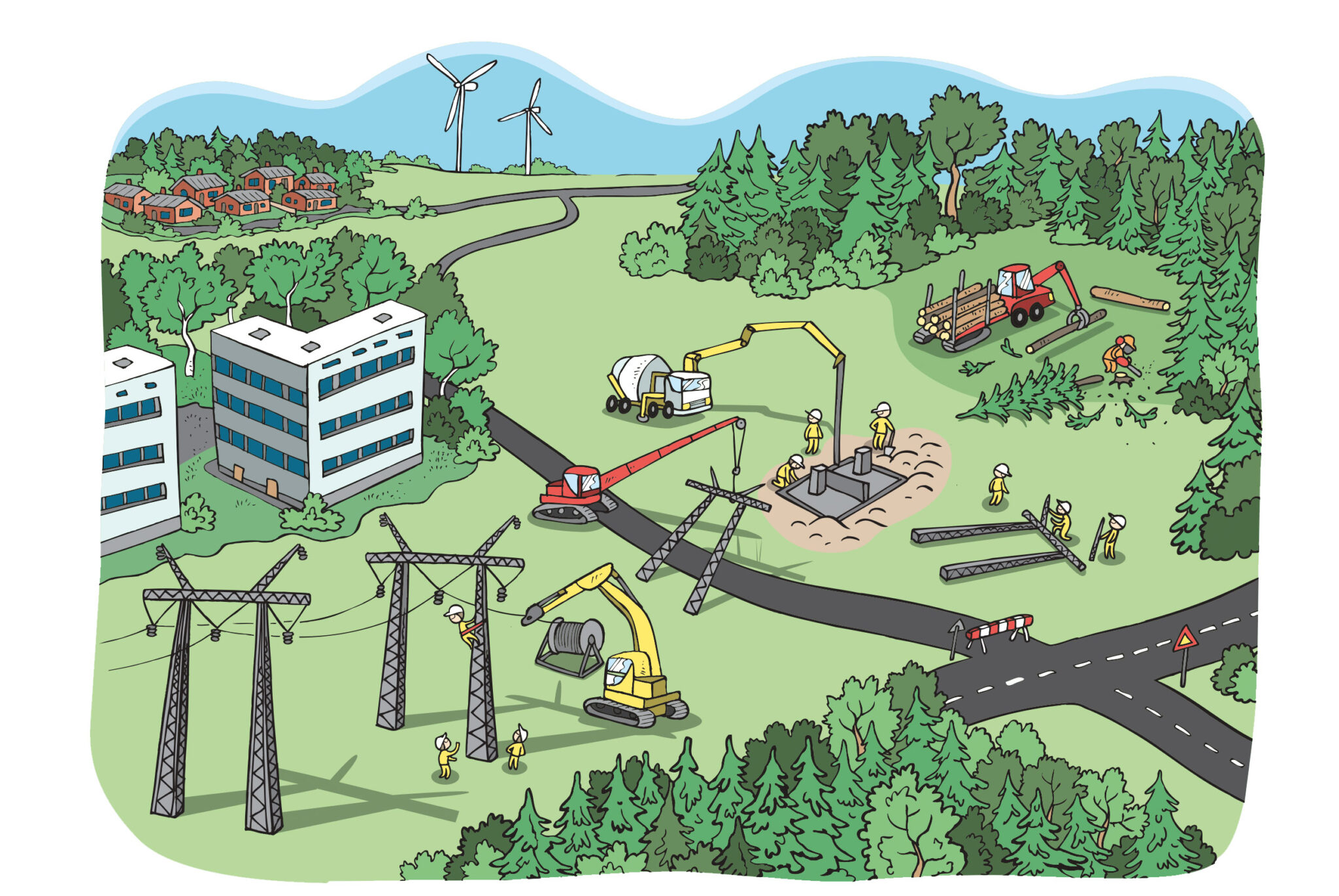

The placement of wind farms requires coordination.

“Not too close to settlements and not on bird migration routes. Nature must be an integral part of the plan in other regards, too. The electricity network connections must be coordinated so that the country is not littered with power lines. The needs of the defence force must also be taken into consideration,” Ruusunen emphasises.

Rinne’s government is investigating how wind power technology can be developed so that the rotating blades do not interfere with the defence force’s radars. If this problem can be resolved, wind farms could also be built in Eastern Finland.

Several international wind power companies are looking for places to invest. Finland will win over investors if we are a more attractive place to invest than countries such as Sweden.

Ruusunen is also satisfied with the government’s programme in this regard. The programme calls for the share of wind power to increase on market terms while eliminating the barriers to wind power construction. The reduction in property tax for offshore wind farms is also a positive factor

“There are good targets. All they need is implementation.”

Ruusunen has proposed the appointment of a rapporteur to assess the role of wind power in electricity generation. In his opinion, the government’s programme shows such a strong commitment to the construction of wind power that there are unprecedented grounds for the commencement of this investigative work.

The security of supply must be safeguarded

The National Emergency Supply Agency wishes to retain at least one-third of the current peat generation capacity on Finland’s energy palette.

The government’s aim of making Finland the world’s first fossil-free welfare society is not without its problems in terms of the security of supply.

For decades, the security of the energy supply has been based on storing imported fuels. Reserves of Finnish peat have also been built up.

The transition to a low-carbon society will increase the use of renewable energy. Wind and solar power, biomass and hydroelectric power cannot be stored in the same ways as coal, oil and peat.

Minna Haapala, the Director of the National Emergency Supply Agency’s Energy Department, says that the adequacy of electric power represent a challenge even now at times of peak consumption: “And this challenge will only increase as society becomes more electrified.”

Giving up on peat would pile on new problems for the security of the energy supply. According to the government’s programme, the practice of using peat primarily for energy will end in the 2030s in line with present forecasts when the price of emissions allowances increases, although peat will remain in use as a fuel for securing the energy supply.

An investigation prepared by Pöyry on assignment from the National Emergency Supply Agency estimated that peat-based generation would decrease through taxation measures and emissions trading from the current annual output of 15 terawatt hours to half or even one-third of this volume by 2030.

In Haapala’s opinion, it will be necessary to retain the possibility to use five terawatt hours in order to safeguard the security of supply:

“Peat is a Finnish fuel that is easy to store.”

Self-sufficiency must not be weakened

Haapala emphasises that wind and solar power are dependent on weather conditions, so the amount of energy generated fluctuates depending on the season and the time of day.

In her opinion, as the energy supply undergoes a transformational shift, care must be taken to ensure the availability of balancing power, which, in practice, means hydroelectric power and CHP generation.

“It is good that Fingrid is willing to reinforce its networks in order to receive all energy generation located in Finland. It is important for generation to be located in Finland and for us to be a competitive country on the European electricity market. Self-sufficiency and well-functioning markets support the security of supply.”

What is the ideal rate of energy self-sufficiency in terms of the security of supply?

“Finland’s electricity consumption varies between 6,000 megawatts on a beautiful summer day and 15,000 megawatts on a cold winter day. Our own generating capacity is 12,000 megawatts.”

“It would not be economical to scale our rate of self-sufficiency according to peak consumption. It is important to ensure that we have enough transfer connections to neighbouring countries and to engage in regional cooperation. However, we should not weaken our rate of self-sufficiency from the current state,” Haapala responds.